In November 1942, with Australia in the midst of a global war, my mother Patricia – then a nineteen-year-old Sydney resident – enlisted in the AWAS. She was selected, as part of a group of about thirty AWAS candidates, to train as an instrument operator specialist, and was posted to North Fort, the Royal Australian Artillery’s battery at North Head.

The battery consisted of observation posts, the plotting room (in actual fact, two rooms) and gun emplacements as well as searchlight batteries and anti-aircraft guns. The AWAS were assigned to the observation posts and underground plotting room to observe and track all offshore shipping movements, both enemy and friendly.

Many years later, she reflected fondly on her experience at North Head in her memoirs, extracts of which I share now…

“The plotting rooms were down two flights of stairs with a heavy door in the passage, and there the password of the day had to be given before admittance. In the first room was a machine known as a TFD (Table Fire Director) at which stood the duty officer altering range and bearing when necessary, aided by several of us girls at other functions.

In the second room, there were three graphed plotting tables, two were vertical and one you had to lie on, and in each case “head and breast” sets were used to pass co-ordinates. These were all hooked up to the telephone exchange, which connected all the outposts as well as other batteries. Sometimes there would be a direct loudspeaker to the guns, and it was quite a thrill to man it and order "Fire!" and the plotting rooms would shake.

From memory there were about five to a watch, so we had the same hours of duty, lectures, stand-down and leave. Lectures were a daily feature of our stay at North Head, and they were on subjects such as range-finding, aircraft and ship recognition, for which in the Observation Post we were armed with enormous binoculars, and searchlights of which there were two, and we had to climb down a ladder and enter a tunnel in the cliff to visit these for instruction.

The winter winds were hard to take, especially when getting up at midnight to walk the cold and dark road to the plotting room, but first remembering to stoke the boiler to maintain the hot water supply … the watch going off would get tea or coffee ready and so we’d settle down with reading or knitting, or even have a nap under the plotter, until the time came to “prepare for action”.

We had never fired a shot in anger but daily had to be prepared for it with continual broken shifts. There were warnings and alerts ‑ with hindsight it would have been when shipping was being sunk off the coast. Japanese reconnaissance planes, flying high and out of reach, also caused alerts ‑ they could be seen and heard.

We had 24 hours leave every 6 days, noon till noon, but otherwise did not leave the fort, except for sometimes taking part in practice shoots at other batteries, such as Cape Banks.

We frequently organised our own battery dances in the Recreation hut, with a live band, Glen Miller being at the height of his popularity, also Louis Armstrong. As well, when not on duty, we had access to the squash courts and indoor basketball court, also concerts and dances at the School of Artillery some distance down the road towards the Manly Hospital. On days of stand down we were able to use Quarantine and Store beaches for swimming, or quietly roam through the bush on the headland.

Those few years in the army were richly rewarding ‑ it was a purposeful life, and we made friendships for life. We all got along very well, and still do when we meet regularly for lunch.”

In my youth, I would often hear stories about the time my mother spent at North Head and I became intrigued by the built and natural environment, which she had so thoroughly enjoyed. When I began volunteering for the Harbour Trust at North Head, all her anecdotes and recollections were vividly brought to life.

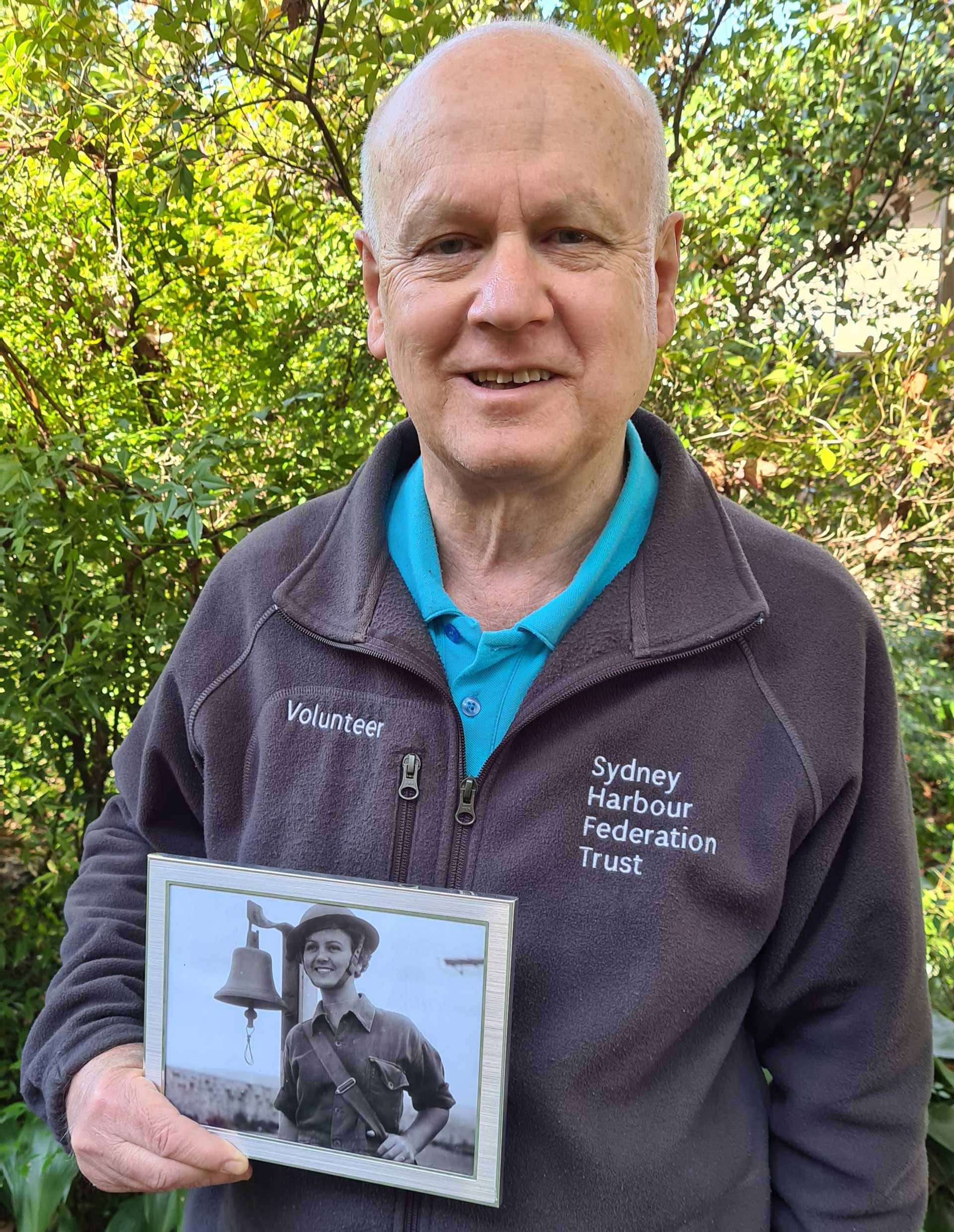

Regarding the image of my mother that headlines this DigiTale, it was published in newspapers of the day with her name, rank and a note that she was located 'somewhere in Australia'. [Editor's note: Although the men and women who ran the Plotting Room at North Fort were crucial to the Allied war effort, their story was not made public at the time due to the highly classified nature of their service.]

Image: Glyn holding a photograph of his mother, taken in 1943.

References

- WEFT - a personal view of a family history by Patricia Evans nee Talberg (1989, unpublished)

- Memories, Memories, dreams of long ago by Patricia Evans nee Talberg (1990, unpublished)

Article was originally published on 24 November 2020.

Our places

Our places  Chowder Bay

Chowder Bay