Ann ‘Annie’ Egan was born on 22 August 1891 in the Gundagai Registration District of New South Wales, the fifth child (there would be nine in total) for parents William Joseph Egan and Ellen Burns. The family subsequently moved to Emerald Hill, in the Gunnedah shire, where Joseph and Ellen owned the “Rosewood” property, and Annie attended St Mary’s College.

The training of Nurse Egan Burns

Annie commenced her nurse training at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital on 17 July 1914. Her sister, Kate, had commenced training at the same hospital the prior year, and was known by staff as Nurse Egan. To prevent confusion, Annie went by Nurse Egan Burns – Burns being her mother’s maiden name. The following year, she transferred to St Vincent’s Hospital to complete her training.

After passing the Australasian Trained Nurses Association Examination in June 1918, Annie enlisted in the Australian Army Nursing Service. Whilst awaiting orders about where to report for duty, she visited her parents at “Rosewood”. Before long, however, she received a telegram ordering her to report for duty at the North Head Quarantine Station in Manly.

The fateful journey of the Medic

Annie arrived at the station on 21 November 1918 and immediately began nursing soldiers from the ‘Medic’. The Australian Transport Ship had departed Sydney for the Eastern Front on 2 November but was recalled before completing its journey when the armistice was signed on 11 November.

Fatefully, while endeavouring to reach Europe via the Pacific Ocean, the Medic had stopped to refuel at Wellington on 7 November. At the time, New Zealand’s capital was grappling with pneumonic influenza (Spanish Flu) outbreak.

By the time the Medic arrived back in Sydney on 21 November, more than 200 passengers including Australian soldiers, Italian reservists and crew were suffering from the Spanish Flu. Within a day or two, Annie herself had contracted the illness. She continued caring for patients but collapsed a few days later and was admitted to the Quarantine Hospital on 26 November 1918.

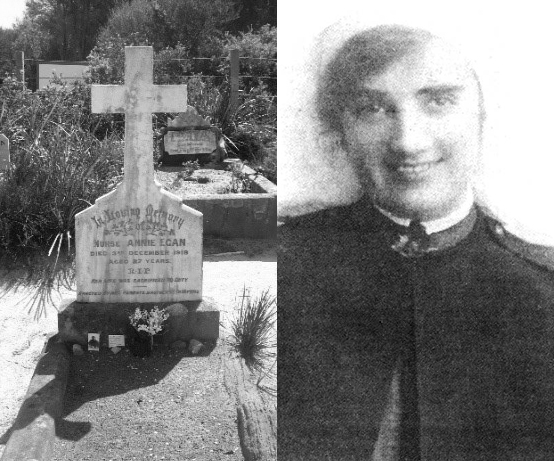

Annie died on 3 December 1918, aged 27 years. She was buried the next day with full military honours at North Head’s Third Quarantine Cemetery. Between 6 and 8 December, requiem masses were held for her at St Mary’s Cathedral and St Vincent’s Hospital and also at St Joseph’s in Gunnedah.

[Image: Egan's headstone; Egan as a nurse, Q Station (source)]

Annie Egan’s enduring legacy

Before passing away, Annie pleaded with the hospital authorities for a priest to be allowed into quarantine to administer the last rites to her and other Catholics. The authorities refused, stating there was no room for resident clergymen of any denomination at the Quarantine Hospital. They cited serious overcrowding and feared that if any clergymen were permitted to enter the hospital, administer the last rites and then leave, this would break quarantine and possibly spread Spanish Flu to the community.

[Image: Page 6, The Sun (9 December 1918), Trove (source)]

On Monday 9 December, Dr Edward Kelly – then the catholic Archbishop of Sydney – approached the gates of the Quarantine Station, accompanied by Father O’Gorman, Administrator of St Mary’s Cathedral. Incensed that Annie had been denied the Last Rites, Dr Kelly and Father O’Gorman formally requested entry to the station so they could administer to the sick and dying.

When the guards refused them entry, Dr Kelly and Father O’Gorman departed before returning a short time later with a reporter and photographer in tow. Although they were again denied entry, the national public outrage was such that the Federal Government backed down and permitted the clergymen into the hospital.

Each year, on the anniversary of Annie’s death, a member of the public places a tribute of flowers and a photograph at her grave at third Quarantine Cemetery. The headstone, erected by Annie’s parents, brothers and sisters, reads “Her life was sacrificed to duty”.

In 2020, Annie’s great-nieces and nephews arranged for a paver to be included on the Australian Memorial Walk, located 350 metres from the cemetery. Located in idyllic coastal bushland with views of Sydney Harbour, the paved pathway is engraved with the names of servicemen and women who served Australia during times of peace and war.

References

- TROVE National Library of Australia – newspaper articles

- Ancestry

- Alison McCallum (researcher)

- Debra Rein (great niece)

Article was originally published on 17 December 2020.

Our places

Our places  Chowder Bay

Chowder Bay